Beyond the blacktop of the Vaatjie Primary School outside of Cape Town, South Africa, is a sandy field. A tall tree hangs over the fence that separates the school from the usually quiet road and two pairs of poles mark the end of the field on either end.

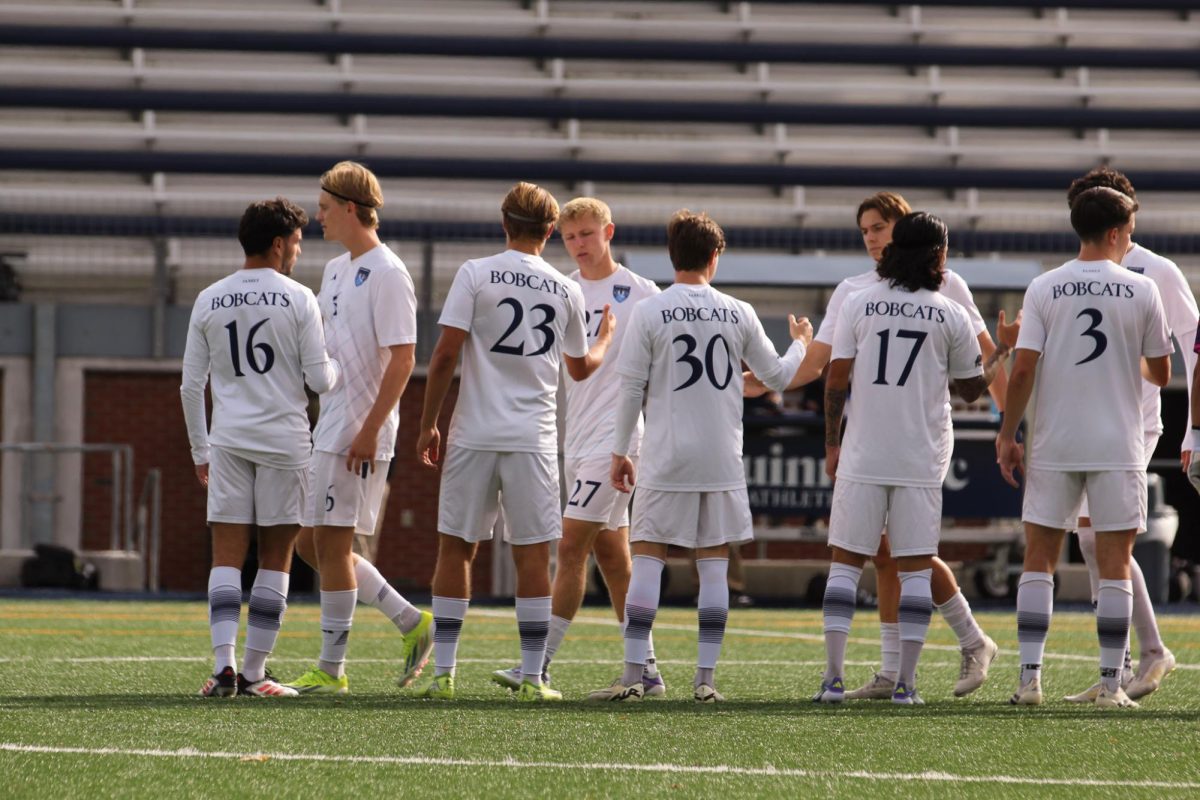

Although the goals aren’t properly aligned, forming an almost-triangle, and sticks coat the first layer of the field, 12 Quinnipiac students – three from the men and women’s soccer teams – are all smiles.

It may not be the soccer field that Erik Panzer, Kat Young and Taylor Healey are used to, but they all make it work.

These three representatives of the soccer teams, along with nine other students, Peter Gallay, Daniel Brown and their coaches, Eric DaCosta and Dave Clarke, were chosen for the school’s first alternative break trip to South Africa. The group ran a five-day summer camp for the children living in the local townships, working in conjunction with the Tippy Toes Foundation, a nonprofit organization designed to help people “regardless of gender, race or socioeconomic status.”

Like the Tippy Toes’ slogan, they were simply “people helping people.”

The kids were assigned to two group leaders and in the mornings were given a choice between soccer or hip-hop dancing before lunch and an afternoon craft with their groups.

Although the children spoke both Afrikaans and English, it turns out there was another common language – one spoken with the feet.

“We obviously know the global impact the game has, but to see how unifying it is, it breaks barriers, cultural barriers, economical barriers, social barriers, language barriers, as well,” DaCosta said. “We say it’s a universal game. You speak the language of soccer or futbol or whatever you want to call it.”

Even with the common tongue of soccer to help bridge two worlds, the staff faced the challenge of structuring drills so the kids would understand and be able to participate without complete chaos. When it came to planning the daily activities for the kids, DaCosta and Clarke knew there was no way to anticipate how the kids would act or react to them and their ideas.

However, Clarke said it did not take long for the children to see that they shared a common passion.

“I think that the first day, we had the warm up and then the little game. We were trying to do things, and me and Eric started volleying and I kicked a kid,” Clarke said, laughing. “But they just saw, again, that we were just players that we weren’t there to tell them what they shouldn’t be doing or what they should be doing. You just let the game be the communicator.”

The first days of camp followed a predictable pattern – the boys hurried to lace up donated cleats and the girls warmed up for their dance routines. Few from either side strayed away from the familiar, so when Young and Healey stepped onto the pitch, it was an unfamiliar sight for the boys of Vaatjie.

“We obviously know the global impact the game has, but to see how unifying it is, it breaks barriers, cultural barriers, economical barriers, social barriers, language barriers, as well,” DaCosta said.

In order the set an example, Clarke urged Young and Healey not to shy away or take it easy on the kids.

“[The boys] didn’t want the girls in the game, but when Kat and Taylor could actually play, then they wanted them and maybe one of the girls could look up to them,” Clarke said.

Though the two needed to prove their skills on the field, it paid off for the girls of the camp. Gradually, the girls began to trade the dancing shoes for cleats and the boys felt the beat.

For Healey, it was a proud moment that stuck with her.

“I think from the entire experience, that’s what I got out of it the most, just having the connection with the kids and being able to see the girls who literally ran away from a soccer ball the first day put on cleats the last day and participate in the tournament,” Healey said.

The final day of the camp, what Healey said was “one of the hardest days of my life,” gave the staff a chance to honor the boys and girls who exemplified the lessons they learned throughout the week. Clarke and DaCosta stressed the importance of respect – respect for the field, each other, the game and themselves. Those who showed respect in everything they did were awarded jerseys in front of the camp.

The kids stood at the head of the group in their black, green, blue and Quinnipiac gold jerseys as a symbol of hope, a reminder of the week they spent with their leaders. Despite poverty, physical, verbal and emotional abuse, in that moment, they could be proud, and those watching could believe that they, too, were worthy.

Though the kids were given a sense of hope, Young and her fellow leaders found that they were the ones changing.

“You can be told that an experience will be eye-opening, but watching a child slip a cold hot dog in their pocket so that they will have something to eat at home or noticing that one of your girl campers can’t look any male in the eye, knowing yourself that she is a victim of abuse, watching the boys put their heads down when talking about their own future, as they cannot avoid the gangs forever, is far more than eye-opening,” Young said. “It is heart-wrenching and life-changing.”

“Everyone knows that there are these problems around the world, but you just try hard not to believe it.” – Erik Panzer

Aside from respect, the players, students and coaches stressed the importance of education. When asked what they wanted to be when they grew up, kids answered pop stars and actresses and most of the boys hoped to be soccer players, according to Healey.

Becoming famous from soccer, movies or music is a quick way out of the trouble the children face, but it is not a certainty. Education is.

“You have the power to change whatever situation you’re in that you don’t like,” Clarke said. “The game is an outlet. It was an outlet for us to get to where we are now, but it wasn’t the only reason we got here … the education was the key.”

The stories the children told of gang violence, drug and alcohol abuse and emotional pain of day to day life. The threats are real, and there is only so much that can be changed in one visit.

“You’re only there for one week out of 52, and the other 51 weeks, the drug dealers and the gang leaders, they’re their role models,” Clarke said. “You’ve got to be of tremendous strength of character to tear down the opportunities that are going to come your way, financially and otherwise.”

While the Quinnipiac students were not ignorant to the fact that five days could not change everything about the situations and hardships these children faced, DaCosta said it was not in vain. Something good did come out of a such a short time.

“We’ve done something that these kids are going to hold with them forever,” DaCosta said. “We’re not going to take them out of poverty. We’re not going to make their lives any easier, but when they go to bed at night and when they’re alone in the corner somewhere or they’re hiding from something, they’re always going to look back at this group of Americans that came in and were open with them and wrapped their arms around them and just accepted them for who they were and wanted them just to be kids.”

Despite what was uncovered as the week went on, Panzer said it was inspiring to see the children come to camp each day smiling wider and wider as they grew more comfortable. It also made their situations real.

“Everyone knows that there are these problems around the world, but you just try hard not to believe it,” Panzer said.

Clarke was not surprised by the immense poverty and the wealth distribution – million dollar shopping malls within miles of township communities, shacks with no electricity or running water. What caught him off guard was the humanity of the situation, things that should be first nature but are often forgotten.

“The people that you see, all these photos and you see all these videos from around the world but then you forget that they’re also people too,” Clarke said. “I think that they wanted to be treated with respect, and it sort of goes without saying and it should be counterintuitive but to walk into the house in the township when we went in, yeah, you could smell the mold and the dampness and feel it, but they were also human. They clean, the bed was made, everything was organized, stuff was on the wall but it’s just not what you’re used to.”

While the homes in the townships kept a level of humanness, according to Clarke, the houses in surrounded areas installed gates, had barbed wires or shards of glass at the top of brick walls to keep people out. The security measures taken alarmed DaCosta, but at the same time, he was pleased with how the group reacted to what they saw – the two extremes of Cape Town.

“I thought that the students would struggle on this type of trip. I didn’t think they’d be prepared for it,” DaCosta said. “I didn’t think that many of them would have seen or expected anything of what we were about to encounter, but man, was I wrong … For a city or a country that has so many walls, [the campers] sure took down our walls pretty quick.”

Click here for more photos from the trip.