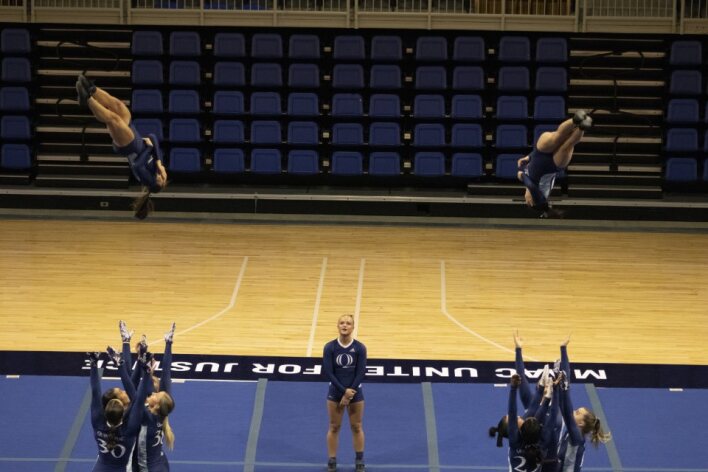

Brittney Kusmierski stood at the corner of the mat. Some of her teammates crowded around the edges to watch as they warmed up. With a running start, she launched into a layout and punched off the ground. The tumble came easy. Her body knew when to turn and which muscles to engage, but the impact of her feet on the mat triggered an unsettling sound.

Upon landing, Kusmierski fell to the mat. She didn’t remember the flip, but she couldn’t get the sound that came from her ankles out of her head. Everyone heard the pop, but nobody moved. She looked up through tear-filled eyes in time to see two teammates run to get a trainer, but she didn’t need a trainer to tell her. She already knew.

Kusmierski had torn her left Achilles tendon the night before the first-ever acrobatics and tumbling meet at the TD Bank Sports Center.

But this wasn’t the first time.

It was Kusmierski’s senior year in high school that served as the sinking, déjà vu-like reference for her pain. It was December 2012 in Omaha, Neb., when Kusmierski took to the Millard West High basketball court during halftime to cheer on the Wildcats. With her mom there for support and her teammates tumbling for the crowd, she too went for a layout, but something wasn’t quite right. When she landed, she was off balance and limped off the court.

She had torn her right Achilles, but trainers and doctors initially missed the diagnosis.

After a month on crutches, an MRI revealed that it in fact was an Achilles rupture, her body had started breaking down the tendon, and she needed surgery.

While she was well on her way to a recovery, she thought her completion of the recruiting process for Quinnipiac’s acrobatics and tumbling team now appeared to be in jeopardy. Kusmierski had her heart set on making Quinnipiac her home 1,344 miles away from home.

“That was my plan, and that was it,” Kusmierski said. “So when [I tore my Achilles], it was just kind of like everything just stopped.”

What Division I coach would inherit an injured athlete? A ruptured Achilles, which means a long, tough rehabilitation, with no promise of a full recovery would seem to make that unlikely for even the most talented candidates. Head coach Mary Ann Powers had a tough decision to make.

But Kusmierski’s mom, Sheila, who is as spunky and spirited as her daughter, picked up the phone and dialed Powers to let her know just how much being on the team would mean to her daughter.

“I had to marinate over whether it would compromise her as an individual,” Powers said. “She’d have to come here and actively engage in physical therapy and be in that [Athletic Training Room] 24/7 to get better first.”

It was decided. Powers offered Kusmierski – soon to be dubbed “Nebraska” by her team – the athletic scholarship. Kusmierski dove into her rehab and classes full-throttle, often going out of her way to schedule therapy so she could still attend practices and provide support from the sidelines. Powers saw her dedication and her love for the team and for Quinnipiac.

“She championed it,” Powers said. “She knocked it out of the park.”

It was February 2013, and Kusmierski had started tumbling again after 13 months of rehab.

“I was just ready,” Kusmierski said. “I wanted to show everyone why I was recruited. I was here. I could tumble.”

She had only been back on the mat for a few weeks – first run tumbling, then stand tumbling. Their first meet was at the end of March, and her nerves were setting in. She texted her dad, afraid she was going to mess something up, feeling like her Achilles would give way, that she wasn’t ready. He sent her a text that she still keeps in her phone to this day.

“He goes, ‘Tumble like you mean it,’” she said, tears in her eyes.

That she did – but in a matter of seconds at that final practice, her worst nightmare was realized. It was like reliving it in a mirror. The first time, it was her right as she pushed off. This time, it was her left.

Everyone was speechless.

“I knew I was going to be fine, I was just going to have to go through rehab all again, but I really didn’t know if I was going to be able to come back [to Quinnipiac],” she said. “That was heartbreaking because I had like just gone through all of the same feelings from last year.”

Enter Billy Mecca, senior associate athletic director at Quinnipiac. He is a cancer and heart attack survivor who practically radiates positivity and faith. His Southern twang serves as an instant comfort. The two met during Kusmierski’s recruiting trip.

“I remember the first time I met her and I saw her,” Mecca said. “There was just something about her that made me go … ‘At some point, we’re going to connect.’”

He was there the night she got the second rupture, and he too shed a tear. Kusmierski turned to Mecca for advice in the following months.

It was hard for her to see her teammates go to practice without her, knowing she might not be able to come back. College is expensive enough – but it’s even more of a burden for someone who needs to fly or drive in from Nebraska.

“I would sit down in his office and just cry and cry … and he would just be like, ‘Nebraska, it’s going to be OK. Everything’s going to work out,’” she said, imitating his drawl.

He was right. Powers brought her back.

“I thought to myself, I’ve got two choices,” Powers said. “If she doesn’t come back, if I don’t offer her that athletic aid, shame on me for recruiting over her and looking to somebody on the outside who might not ever have that kind of heart. She might not ever be able to bring us a score that you could really look at and see on that scoreboard … but the scores that she was bringing this team [were] so far more valuable.

“You could be the scorer that is all about leadership and inspiration and calming down another player, who you know that a coach might not know has things going on in their lives. Brittney was that unseen scorer her first year here.”

During her rehab and recovery, Powers said Kusmierski became the source of motivation for the whole team.

“She didn’t need motivation from us,” Powers said. “We looked to her for that.”

Kusmierski appears every bit the poster child for perseverance – but despite her outward optimism and mile-wide smile, her injuries still weigh on her mind.

“I’m back, but the fear of tumbling is still there,” Kusmierski said, prior to her first meet of the 2014 season. “The first time around I was ready to tumble … but this time it’s more of a mental thing.”

The impact tumblers make on the mat is hard on the Achilles, and Kusmierski says she is a “hard tumbler.” She didn’t tumble in her first meet back because of nerves, but she still had a smile on her face.

“I mean, obviously nothing’s going to be as strong as your original ones, but they’re like two brand new cars,” she said.

With tears dried and now just a memory, Kusmierski began the hard work of wiping away her worries and taking her new tumbling tendons on a test drive in competition.

“[My scars are] like a part of me now. I like that they show what I’ve gone through and they’re a reminder to me how far I’ve come.” – Brittney Kusmierski

As her scars have smoothed over and healed, she has grown.

“We can put all of our plans in pencil on a piece of paper, and the thing you’ve got to always remember is God has an eraser,” Mecca said. “What Brittney’s been able to overcome and accomplish has been incredible because … she’s persevered. And from her perseverance she’s developed incredible character and that character has led to incredible faith and I think that faith and hope has transformed her and made her into the person she is today.

“The greatest comfort I have is that Nebraska is always going to be OK, that athletics is nothing but a memory and whether she creates any memories on that mat, she is already creating incredible memories at this institution.”

Before coming to the East Coast, she had never seen a Dunkin’ Donuts, eaten at a diner, hopped on a train or called a taxi. But now she has, and she has two ruptured Achilles to her name and a great story – something she has shared with her friends and freshmen as an orientation leader at the university.

“I can’t imagine not being here and having gone through both of [the injuries],” she said. “I just, it makes me grateful that I have people here like Billy … all the coaches, all of the teammates.”

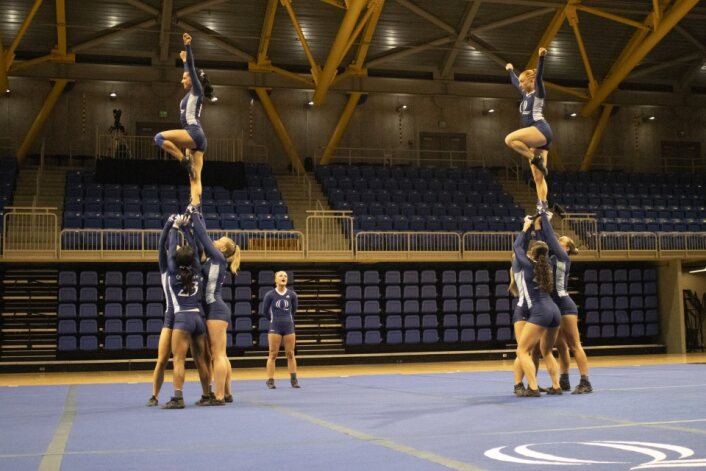

When Kusmierski watches her teammates at practice, she huddles with the others on the side of the mat, hands secured on her thighs, an ear-to-ear grin on her face, shouting at her 32 teammates and giving back the support they have given her. When she is on the mat with them as back base, she catches the flyers in her arms every single time.

At the first home meet of the season against Gannon, Kusmierski was perhaps the happiest person in the room, as she watched her teammates tumble and then, finally, took to the mat herself for some acro, pyramid and toss rounds, and the team routine. Powers said Kusmierski would be the voice of reason from the back, putting her teammates at ease.

“I like to think that a good majority of the team is unselfish … in this sport they have to be. They have to trust each other,” Powers said. “But [Kusmierski’s] unselfishness extends far beyond that. She is the go-to person for anything, whether it’s a coach’s need, whether it’s a team member’s need, moreso right deep into the heart of the Quinnipiac community.”

Kusmierski has landed on both feet without resentment. When asked to see her scars she reveals them with a sense of respect. They are badges of courage. She didn’t like using a too much vitamin E on them because she wants them as a reminder.

“I didn’t want them to completely disappear,” Kusmierski said. “They’re like a part of me now. I like that they show what I’ve gone through and they’re a reminder to me how far I’ve come.”

Achilles injuries typically occur to men between the ages of 30 and 50. Kusmierski, 19, seems to value how this extraordinary insult to her foundation helped build and expand her appreciation of the ordinary around her.

Now, she prepares to add to her role as back base, trust herself and tumble like she means it for the crowd in competition.

“I think the greatest compliment I can give Brittney is she might be the best teammate we’ve ever had in any of our athletic programs at Quinnipiac,” Mecca said. “That’s the ultimate compliment: that before you can be a great team, you have to have great teammates, and Nebraska does what’s right, the right way, at the right time. That’s a very special kid.”