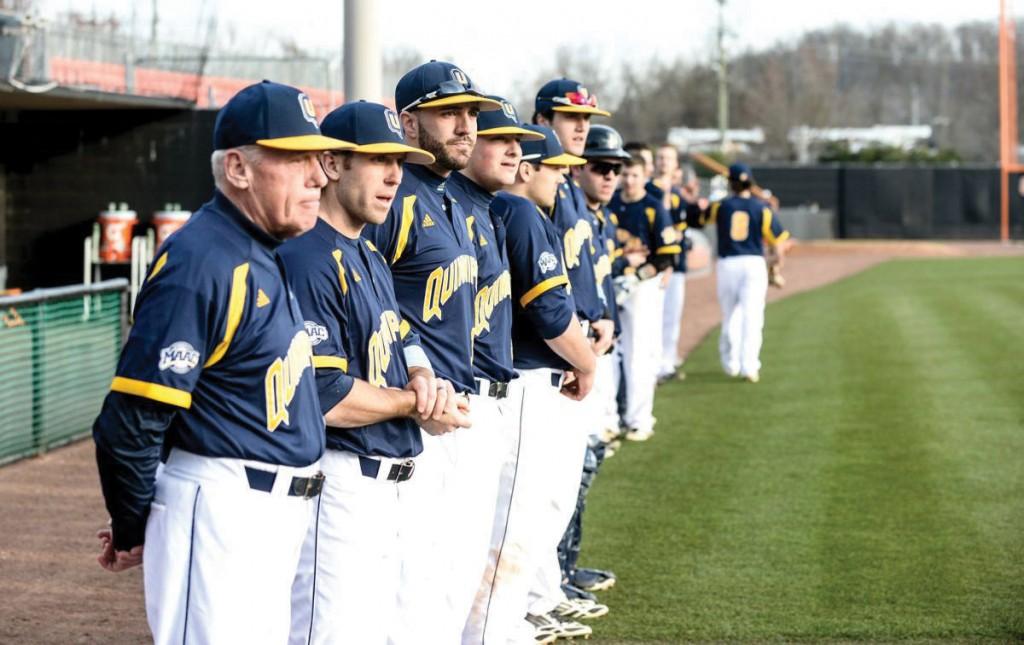

[dropcap]D[/dropcap]an Gooley sits in the cool shade of the visiting team dugout. Ball cap secure on his head, he leans back on the bench and loosely grips a bat between his hands. A timeless scene unfolds in front of him. Green grass. Blue skies. The snap of a ball hitting a glove.

This is Gooley’s kind of day in a life full of these kinds of days. Glancing at the scene around him, he pronounces it his “pure, unadulterated home.”

But those days are running out for the man universally known as Skip around the Quinnipiac University campus in Hamden, Conn. Gooley is retiring at the end of the 2014 baseball season after a career worthy of an old-time baseball movie – but not the one you’re thinking of.

It’s not the one where the underdog hits the pinch-hit, walk-off home run to send the team to the World Series. It’s the one where the good guy from the common clay struggles, yet ultimately inspires loyalty in his players and keeps the purity of the game alive, even if just for a little while.

When Quinnipiac athletic director Jack McDonald first met Gooley, he thought he was too good to be true and pinned him as an Eddie Haskell from “Leave it to Beaver”: a gentleman in public, but a villain on the side. It didn’t take him long to realize just how wrong he was.

“This is a quality guy,” McDonald said. “He’s everything you’d want in a head coach. Everything I’d want as a head coach for our student-athletes – follows the rules, energetic, knows the game, always positive.”

Whether his team is on a hot streak or enduring a slump, Gooley’s mentality is simple: learn, but focus on the next pitch, the next game.

“Say we’re playing a doubleheader,” junior pitcher Matt Lorenzetti said. “We lose the first game, in extra innings, on a walkoff home run. Totally demoralizing. If you saw Skip 25 minutes later and we’re getting prepared for the next game, you wouldn’t have even known.”

Players often feel at home the moment they meet the man. Such was the case for Lorenzetti when he visited Quinnipiac as a prospective recruit.

“Once I was here I didn’t want to leave,” Lorenzetti said. “He’s very passionate and you can really see it in terms of players who just came back. We get guys coming back to practices, we get guys coming to visit us in games … players are still so loyal to him even after they’ve graduated [and it’s] a real testament to the kind of guy he is.”

Gooley, 67, is a baseball and Quinnipiac lifer, a university Hall-of-Famer whose career spans generations. Coming into this season, his Quinnipiac coaching record was 406-442-7, making him the school’s all-time leader in coaching victories.

He grew up in New Haven, Conn., and attended first Hillhouse High School, then Cheshire Academy for a year before he was recruited for the Quinnipiac baseball team by the athletic director, Burt Kahn.

“If you’re in a baseball dugout, whether it’s snowing or ice or rain or sleet … the baseball gods are smiling. They smile at you.” – Dan Gooley

Gooley first set foot on the Quinnipiac baseball field in 1966, decades before the school became a university and changed its team nickname from the Braves to the Bobcats.

Baseball was a bit different when he starred as a pitcher on the Quinnipiac team – before there were thick rosters (14 players then, 27 now), lengthy seasons (25 games then, 56 now), specialized pitchers and aluminum bats. When he graduated in 1970 with a degree in marketing, he was part of the first-ever class to spend all four years on the Mount Carmel campus.

“It was great,” Gooley said of his college experience. “I had a very solid career … we won two championships. It was awesome. My college baseball playing days were the best.”

The following year, Kahn hired Gooley to serve as assistant coach of the baseball team. His job description expanded to assistant soccer coach, physical education teacher and sports information director as well. He soon became head baseball coach.

Gooley coached at Quinnipiac for 16 years, leading his team to the 1979 NCAA Division II Regional Tournament and then the NCAA Division II College World Series in 1983. Among his top players: Turk Wendell, who went on to a sturdy career as a reliever in Major League Baseball.

In 1988, Gooley left to coach the Division I baseball team at the University of Hartford. There he coached Jeff Bagwell, who has since played 15 years in the MLB and earned National League MVP honors in 1994 with the Houston Astros.

“You get lucky once in your life to have Turk Wendell, and you get lucky to have Jeff Bagwell,” Gooley said. “I mean he’s the greatest player I ever coached. I don’t know if I ever coached him to be honest with you.” He laughed. “I don’t think I did. I think I got smart, I just got out of the way, let him do what he wanted.”

Yet even in a life defined by the wisdom he has imparted from the dugout, Gooley took a detour once that proved he could succeed in any facet of the game.

After five seasons, he left Hartford in 1992 to join the Starter Corp. in New Haven. At the time, Starter stood as one of the premier official suppliers of apparel for professional sports teams. Gooley worked in the pro-team service division and oversaw the Major League Baseball apparel account. In his last year he became director of the entire pro-team division.

At Starter, Gooley’s combination of charm and persistence revealed itself, all on behalf of his dad, Raymond. His humility also showed, because very few actually know what he did there.

In 1995, Gooley’s ailing father gave him The Ultimate Baseball Book for Christmas. Gooley said he wanted to do something special for his father, at the major league level.

“Well, what do you think about changing the look of the Yankees’ jacket?” Raymond proposed, as he casually flipped through the pages of the book. The Yankees had worn jackets with the interlocking NY since the era of New York greats like Yogi Berra, Joe DiMaggio and Mickey Mantle.

Gooley told his father the Yankees would never change.

“Hold on a second,” Raymond said. He opened up to a page with images of the 1956 World Series, won by the Yankees. The team’s jackets featured the word “Yankees” in script across the front. “You know, this would be something very special.” Special, indeed.

The Yankees had last won a World Series in 1978. Perhaps creating a throwback jacket to a winning team could bring some good luck. It will help them win in 1996, Raymond said.

Raymond’s off-the-cuff comment struck a chord with his son. This was a venture Gooley was determined to take on.

Nobody thought the Yankees would be willing to change. Nobody. But Gooley wasn’t without support.

All he really had to do was convince the man who had the highest standard of excellence: George Steinbrenner, owner of the Yankees.

Gooley worked with the marketing and art departments at Starter to develop the design, and it had to be perfect. He went himself to the Yankees front office with prototypes, but the color wasn’t right. It was navy when it should have been midnight black.

It was Old-Timers’ Day and the Yankees’ former greats, like Reggie Jackson and Whitey Ford, noticed the prototype hanging up in the corner of Steinbrenner’s office. They asked him about it and suggested that if it had been good enough for them to wear, it was good enough for Steinbrenner’s current team.

Meanwhile, Gooley and the team at Starter were back at work on the final prototype – with a full Yankees script, perfectly positioned buttons, striped collar and arm emblem – and it was delivered to Steinbrenner on Labor Day weekend in Boston.

Gooley got the call that Monday morning. Steinbrenner had given his approval.

Joe Torre unveiled the jacket at the start of the 1996 playoffs. The Yankees’ equipment manager and Gooley’s constant supporter, Nick Priori, invited Gooley to Yankee Stadium for a press conference in the dugout the day before the playoffs. Gooley walked into the clubhouse with his all-access pass and saw his jacket hanging in the lockers of each player and coach.

Gooley took his place in the corner of the dugout, which was mobbed by the media, all waiting for Torre.

It was time. Torre walked down the runway and took a seat on top of the dugout, proudly sporting a brand-new jacket. Cameras flashed. “This is our new look for the ‘96 playoffs and World Series,” said Torre, who then looked at Gooley and gave a wink.

The Yankees went on to win the World Series and sell 26,000 jackets during the Christmas season, Gooley said, and Steinbrenner bought 300 of his own at retail to give to the Yankees Tampa Foundation, Inc.

“It was fabulous. It was absolutely fabulous,” Gooley said. “And I mean all of the players had [the jackets] on and wore them on television, the World Series, the whole thing. It was great. But it was all, see the idea was my father’s,” he said. “… He was very sick at the time, so I had said, ‘I’m gonna do this for him.’”

Raymond died six years later.

Gooley returned to Quinnipiac in 1998 first as director of athletic development. During this time, he navigated the school’s transition from a NCAA Division II program to NCAA Division I. Quinnipiac College became Quinnipiac University. When he became baseball head coach again in 2001, the school adopted a fresh nickname: the Bobcats.

Gooley blended his decidedly old-school approach with players into the more modern baseball game, and it worked spectacularly well – for a time.

In 2005, the Bobcats won the Northeast Conference Tournament, 7-2, to qualify for their first-ever NCAA Division I Regional Tournament.

Two years later, they shared the Northeast Conference’s regular-season title and were voted the top Division I team in New England by the New England Intercollegiate Coaches Association.

In between those two peak years, however, Gooley was faced with a situation that every college coach dreads: players behaving badly off the field.

In 2006, the university suspended several baseball players after photographs of an alleged hazing incident surfaced online. The news spread through local media. Gooley immediately offered to resign, but McDonald would have none of it.

“He walks into my office and he says, ‘Jack, I’m going to quit. I let the university down when this happened,’” McDonald recalled. “I said, ‘Dan, you cannot quit. I need you and your student athletes need you at this very important time. So get out of my office, and let’s help these guys understand that they made a mistake, that they’re going to be disciplined, and that we want them back when the discipline’s over.’ And he did. He sort of captained the ship during a real bad storm and he handled it remarkably.”

Since 2007, Quinnipiac baseball has struggled. During the past three seasons, the team lost more than twice as many games as it won in the NEC.

Ask Gooley, and he’s quick to say it’s his own fault – but there were other factors at play.

His student-athletes play on a field and sit in a dugout about as old as their parents. Recruiting players to compete on a field that is not as good as many high school diamonds has become a real drawback. Plans for a new field have continually come and gone, and the university’s athletic department put everything on hold while a Title IX lawsuit worked its way through federal court. Though Quinnipiac settled the lawsuit in 2013 and has introduced plans for new athletic fields, a baseball field may not be included. When Gooley was director of athletic development, he helped raise money for the new athletic facilities at York Hill, yet none of those funds went to the baseball team either.

But that’s not all. Gooley has never had a full-time assistant coach to actively recruit for him. And on top of that, the amount of scholarships available to both attract and secure talent also falls short of the total players he needs to recruit.

Asked whether the university had plans to grow the baseball program, McDonald responded: “As with all our teams we hope to elevate our resources for our teams in a timely and equitable way.”

There are 57 Division I schools in the Northeast alone and given the limited resources at Quinnipiac, it’s no surprise recruiting has become a challenge.

But to Gooley, baseball is baseball, no matter where you are.

“If you’re in a baseball dugout, whether it’s snowing or ice or rain or sleet … the baseball gods are smiling,” he said. “They smile at you.”

During the last few years, the generational shift has had an impact on the team, with some players not subscribing to Gooley’s teaching methods. The resistance became more marked as the losses mounted.

“I always say that it’s simple: the players got all the wins and the coaches got all the losses.” – Dan Gooley

Gooley steadfastly endured these losses, never once blaming his players, the field or the university. There is never an excuse. He internalizes it all.

“Win, lose or draw, some you win, some you lose and some you get rained out, but you dress for them all,” he said. “And the pride I have for this university is immeasurable, so just because you have a couple of tough years and you hit a tough patch, that doesn’t change how you feel about where you’re at. It never will.”

For Lorenzetti, attitude over aptitude is the true key to success – something he thinks his team had been lacking the past few seasons.

“We had better talent than most of the people we were playing,” Lorenzetti said. “… It’s just that we didn’t really have the right guys in terms of buying into one system and buying into believing in each other.”

Though there may have been some occasional bad luck in recruiting, Lorenzetti believes they are rectifying the issue now. One look at the team’s record shows progress; they nearly doubled the amount of wins in the last two seasons. Now that the team finally has a solid recruiting class, they are showing potential.

“[Gooley] probably could [place blame] if he wanted to … but that’s not who he is,” athletic director Jack McDonald said.

Gooley, however, would disagree.

“I always say that it’s simple: the players got all the wins and the coaches got all the losses,” Gooley said. “You know, unfortunately, I probably haven’t done as good a job as I should. There’s nobody harder on me than me and you know, I’m disappointed, I feel badly, but it just hasn’t worked the past couple of years.”

Despite it all, the triumphs and the challenges, Gooley consistently places an emphasis on the students’ success beyond the diamond.

“The key ingredient to this whole mix is those guys have got to graduate. If they play here and go to school here and they’re here for four years and they don’t graduate, then I’m a failure,” he said. “… They failed themselves and we have failed them. And I will never have that. I will never have that.”

Gooley is a humble head coach with a big heart. His love of the game is evident in the joy that he shares when he speaks of his journey, regardless of the ups and downs. He views the game of baseball with a sense of respect rooted in the opportunities it has given him – and though he knew it was time to retire last June, he couldn’t help but give it one last go around.

“I still get the thrill of a victory and I’m still upset when you lose,” he said. “And I’m convinced you can be as excited as you want to when you win, but if you accept losing and you don’t care if you lost, then you should get out. Because it doesn’t mean anything to you. But if you lose and two days later, you’re still upset with it, then you gotta stay in it. Because it means something to you. Right?”

When current assistant coach John Delaney takes over as head coach next season, the team will still have that mix of old and new. Delaney played under Gooley, too.

Gooley is retiring after his team’s first season in a new league, the Metro Atlantic Athletic Conference. As he makes the transition to full-time fan, he leaves behind a legacy and a life lesson of effort and excellence, no matter what the stats say.

“You either win or lose. You’re either safe or out,” he said. “You go on a field and you be as competitive, inside the rules of the game, as you can, because when you leave, you have to live inside a society that has rules … If you go out and you do your very best at something you love, then you’ve got a chance to be successful. You got a shot.”