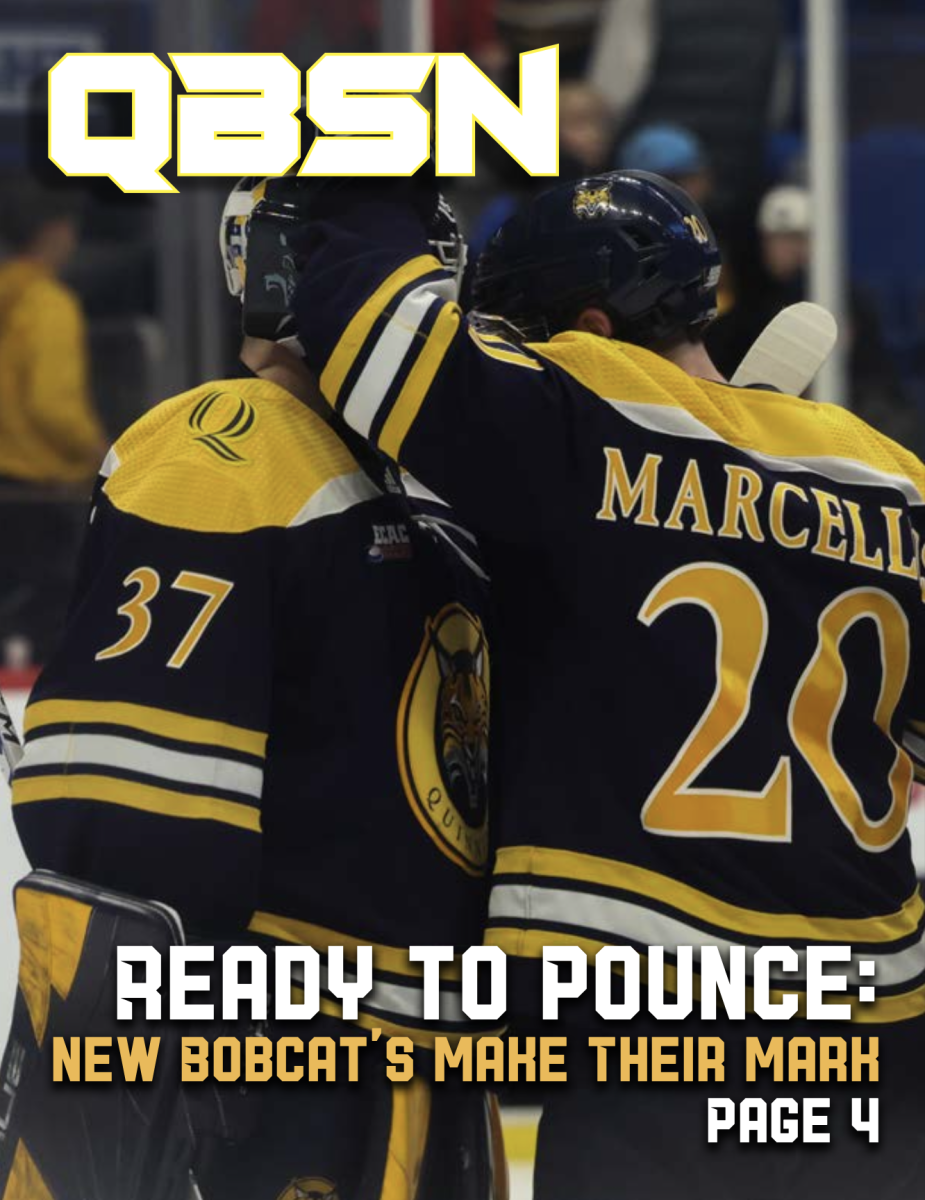

When you ask a hockey player about the early days, everyone seems to answer the same.

Waking up before the sun rises, eating a quick bowl of cereal, hopping in your parent’s’ car and heading to the rink. You walk into the locker room, your mom or dad helps you tie your skates, and you stumble down the hall, through the door, and onto the ice.

For at least a decade, each hockey player follows the same path, moving their way through the local in-house leagues, with some choosing to stay, and others leaving for travel programs that play harder competition.

But then what happens?

For each college hockey player, that’s where the story starts to change. Some choose to play for their local high school. Others find a junior hockey program and work their way up to the top tier. Then, there’s a third party of players, who decide to do both.

We’ll start in high school. Over 35,000 boys, as well as over 9,000 girls, are part of a high school hockey program, according to Statista. The effectiveness of playing high school hockey depends completely on the program. The program must have a coaching staff that knows how to prepare a player for the next level, be it Division I or another destination. The amount of time and effort that are asked of a player is critical, as is the competition that the team is playing against.

For a player to choose to stay in high school, they’re also making the conscious choice to remain a student-athlete. Eight hours a day in the classroom, at least one hour a day at the rink, extra time for training and team functions.

And that doesn’t even include homework.

But for some, getting a chance to play for a major varsity team outweighs all of those burdens. Being a part of a state championship-winning team is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, and for college coaches, bringing winners into their program is a dream come true.

One player that developed their winning ways in high school is Kenny Agostino, a forward in the Boston Bruins organization. Years before turning professional, Agostino was a freshman at Delbarton School, a major preparatory high school in Morristown, New Jersey. Given that Delbarton is a championship-caliber team each year, Agostino knew from day one that he was joining a group of players and coaches that shared a common goal.

“Learning how to win, and expecting nothing less than winning. That was our philosophy,” Agostino said.

Agostino was a powerhouse in high school, recording 261 points over four seasons, the school’s all-time record in that department. He was also a part of three state championship-winning teams during his sophomore, junior and senior seasons. He also took home the Player of the Year Award for the state of New Jersey in his junior and senior seasons.

Needless to say, high school taught Agostino how to win, to the point where the Yale Bulldogs wanted him right away.

“Originally, I was slotted in to play juniors, but during my senior year, they saw me play and they thought I was able to make the jump right to college,” Agostino said.

He brought the winning pedigree with him to Yale and ECAC Hockey, and more success followed close behind. Agostino had 132 points in 134 career games, including 41 points during the 2012-13 season, a year in which the Bulldogs won their first national championship in program history.

While winning is always a nice perk, high school players who stay in their hometowns get the opportunity to play with the same guys that they’ve grown up around. They also get to play in front of student sections made up of hundreds of their classmates. For players lucky enough to have this opportunity, it’s one they can’t pass up.

Quinnipiac hockey’s sophomore forward Alex Whelan was one of those players. Whelan played four seasons at Ramsey High School in Ramsey, New Jersey, his hometown. It was the place he had wanted to play his entire career, and he took full advantage.

“It’s a different experience than most guys have,” Whelan said. “It’s kind of a cool one though because you get to play for your hometown and with all of your friends that you grew up with.”

Not only did Whelan play with his friends, he put on a clinic for them. He racked up 265 points in 110 career games and was awarded the State Player of the Year Award during his junior year. He was also named to the first All-North Jersey team his sophomore, junior and senior years. While this put him on the radar of countless college programs, it also benefitted him on a personal level.

“I would say self-confidence,” Lisa Whelan, Alex’s mom, said on what her son gained from playing high school hockey. “He excelled [at Ramsey], and he realized that he was pretty good at this whole hockey thing.”

Whelan’s confidence and maturity continued to grow throughout his time with Ramsey, and he could’ve easily chosen to leave for a preparatory high school or a juniors program. Despite all of the benefits that those options provide, Whelan stayed put, playing four full seasons with the program that he had grown up idolizing.

“Alex always wanted to play for Ramsey,” Lisa Whelan said. “He used to see them at the rink, and he would fist bump them as they got off the ice, so he was always hoping to play for them.”

After his senior year, Whelan did end up making the jump to juniors, a common move for college hockey players looking to further their development before arriving on campus. While some, like Agostino, are ready to make the jump right away, many others choose to spend the extra time preparing for their college team in order to gain maturity and experience.

“A lot of the guys on my team were older guys,” Alex Whelan said. “They kind of took me under their wing and taught me a lot.”

The leadership and maturity have already shown for Whelan as a member of the Bobcats. He tallied six points in the final seven games of his freshman year, and is now one of the team’s leading scorers, playing significant minutes on both the power play and penalty kill. As each game goes by, that same self-confidence and maturity are beginning to show through.

The message of maturity is echoed far and wide by players that have gone through a junior hockey program. Instead of beginning their careers in high school, some choose to play strictly junior hockey before coming to college.

Most players who choose the juniors route in Canada will move away from home at 16 or 17 years old. They live with billet families; local families who open up their homes to junior hockey players who are not from the area. Much like life as a college student, junior hockey players are tasked with figuring out life on their own.

One of the players that lived this life was Quinnipiac hockey’s junior forward, Craig Martin. Martin started his junior career at just 15 years old, playing in the Kootenay International Junior Hockey League, a Junior B league based in British Columbia. After playing in parts of two seasons in the KIJHL, he left home for greener pastures.

“It was a good experience to move away and mature a bit,” Martin said, “figure things out on your own.”

Martin transitioned to the British Columbia Hockey League, putting up 98 points in 137 career games with the Trail Smoke Eaters, Vernon Vipers, and Alberni Valley Bulldogs. Whether you’re playing in Canada or the United States, the level of play in juniors is a great test for those looking to play in college. But just as Whelan and Agostino learned, there’s more to it than just the on-ice benefits.

“A lot of it is learning to be on your own,” Kim Martin, Craig’s mother, said of what her son gained from playing junior hockey.” Taking responsibility for getting your assignments done, time management, organization skills, leadership.”

While the changes to their personal life are certainly something that players have to overcome, the main benefit is clear. If you’re playing juniors at a high level, the academic burden is not nearly as high, and you can focus more on hockey. It’s the closest a player can get to being a professional at that age, but also shows them the commitment it will take to play for a Division I program.

“You’re not in school as much, so you can focus more on hockey and prepare each day to bring it every day and get better,” Craig Martin said.

But what does not in school as much really mean? After all, in order to attend college, you do need to graduate high school first. Well, there are many options on the table for junior hockey players, and a lot of it depends on the program that you’re a part of. Some send their players to local high schools, while others promote taking classes online.

“The schedule is quite demanding,” Mike Martin, Craig’s dad, said of his son’s education. “They have practices during the day, so he did have to take online classes in order to stay level with the other kids and graduate.”

While you’re still getting an education, it’s likely not in a classroom, which could hurt you when you get to college and become a student-athlete. Then again, the less time you spend hitting the books, the more time you have to focus on hockey.

So, which option is better?

Honestly, it depends on the player you ask. Despite all of the differences between high school and juniors in terms of style of play and life outside of the rink, one thing remains the same among the players. They wouldn’t change a thing.

“If you’re fortunate enough to go right from high school to college, it’s obviously a special experience to be a true freshman, so I’d definitely recommend it if somebody has the opportunity,” Agostino said of his path.

“Absolutely not,” Martin said on his journey. “I learned a lot, and I loved it.”

So, on those freezing cold winter mornings, when you and your parents walk into the local rink, ready for another morning playing the game you love, you’re likely not thinking about which junior program is best for you or whether your high school varsity program is the place to play.

Later on in life, however, where you decide to go could have a direct impact on where you end up playing college hockey if you even end up playing at all. So, that leaves us with just one question left to answer.

Where would you go?