If you look at an acrobatics and tumbling roster, you’ll notice a pattern amongst the team: not one athlete trained and competed in the sport prior to college. In fact, it only exists at the collegiate level.

In the past, entering college signaled the end of gymnastics for many women across the country. There are a limited number of gymnasts that reach the elite or collegiate level, and the rest move on to competitive cheerleading or continue gymnastics. The creation of this new sport opened the door for former gymnasts and competitive cheerleaders to continue competing in a skill set they trained for their entire life.

The National Collegiate Stunts and Tumbling Association announced its transition from competitive cheerleading to acrobatics and tumbling in 2009. Along with five other universities, Quinnipiac became a member of the National Collegiate Acrobatics and Tumbling Association and one of the first colleges in the country to make the switch.

Quinnipiac head coach Mary Ann Powers is one of the founding coaches of the NCATA and has been with the team since its competitive cheerleading days. Throughout her 22-year coaching career, Powers has been able to witness the growth and development of acrobatics and tumbling.

“I think [acrobatics and tumbling] is the most well attended female sport on the campus,” Powers said. “I think people are fascinated by the strength, the agility and the fearlessness of what these women can do. We are a nice blend of different sports and now there’s an opportunity for women from gymnastics and cheerleading at the collegiate level that never existed before.”

Since the program’s debut season, the Bobcats have made the NCATA Championship Semifinals every season except 2015 when they fell to Azusa Pacific University in the quarterfinals. This season, the team defeated the University of Oregon in a tri-meet for the first time in program history. Quinnipiac also superseded the Ducks to secure their hard-earned spot as the No. 3 ranked team in the country.

The success of acrobatics and tumbling is largely in part due to Powers. In college, Powers captained her competitive cheerleading team at Southern Connecticut State University for two years. She knows all about what it takes to be the best of the best at the collegiate level. Powers is also a certified USA Gymnastics coach and has coached both Pop Warner and all-star cheerleading. Her coaching background in both sports has eased the switch to acrobatics and tumbling and put Quinnipiac on the map for gymnastics and cheerleaders to join a prestigious program.

“If you want to get recruited in college gymnastics and cheerleading, it’s pretty elite,” Powers said. “There are a lot of kids in acrobatic gymnastics that aren’t going to be making a world’s team. There are a lot of kids from competitive cheer that don’t want to be leading cheers and want to actually compete skills. They are the show, we want them and because we’re one of the best programs in the country, we get them.”

Unlike other sports, acrobatics and tumbling brings women from different athletic backgrounds to one individual sport that blends all their talents together. Senior Jenna Adams felt more comfortable stepping onto the mat her freshman year with prior stunting experience. As a former competitive cheerleader, she’s familiar with the acrobatics side of the sport that involves stunting.

In contrast, former trampoline and tumbling gymnast Stephanie Van Albert had to adjust to a lot of the aspects of acrobatics and tumbling.

“For me, I’d say I had a really tough transition. I came from trampoline and tumbling which is a type of gymnastics,” Van Albert said. “Going from a bouncy trampoline to the floor where there’s no bounce at all, that was really hard for tumbling. I never stunted before so when learning [acrobatics and tumbling], that was all new.”

Brianna Gerndt, a former gymnast and high school cheerleader, had an easier time acclimating to the sport with experience from both backgrounds.

“I truly believe that without gymnastics, I wouldn’t be here just because it’s so tedious,” Gerndt said. “It’s very strength and repetition based. The stunting aspect is kind of like high school cheerleading, just not as intense.”

Nine years later, 23 colleges and universities recognize acrobatics and tumbling as a varsity sport, which comes with being treated just like any other collegiate sport. Teams are equipped with trainers and strength and conditioning coaches, who are probably the most important people to the athletes. Quinnipiac’s training department helps the athletes build strength to compete at the rigorous collegiate level and encourage them to eat healthier and exercise consistently.

“Without them, we would not be as strong mentally and physically,” Adams said. “We wouldn’t be able to perform the way we have especially this year. Everyone on the team takes it upon themselves to go the extra mile; eat better, exercise a little more outside of practice, come into practice and work the entire time whether you’re in or out.”

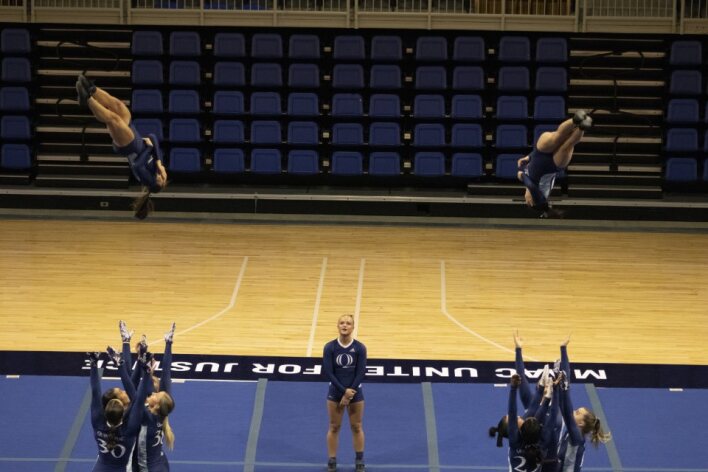

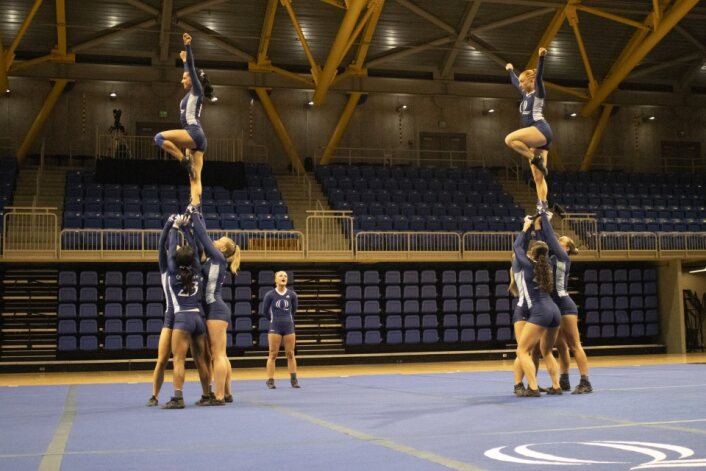

One important aspect of training is teaching the women to have the necessary skills to achieve the highest score possible. Meets are comprised of six events: compulsory, acro, pyramid, toss, tumbling and team. The events are split into different heats where the athletes are scored based on the difficulty and execution of the skills performed. Every perfect 10 depends on strength, agility and patience.

The most difficult part of acrobatics and tumbling is to perform the skills with synchronization and precision. The judges who finalize the points are very strict in what they need to see from these athletes. If the athletes bobble the smallest amount in a stunt or take too many steps out of a tumbling pass, points are deducted from the starting score. If the team routine is performed even the slightest bit out of sync, it could cost them crucial fractions of a point.

Each individual score is a smaller piece of a bigger picture. Every score added up contributes to the overall number the team receives at the very end of the meet. One athlete may contribute to one-tenth of a score while others may provide for more points, but that does not make that one-tenth of a point any less important. This is a sport that competes for every possible point they can get, and it shows in how close some of the final scores can be. Teamwork involves having the correct mental frame of mind and the strength to step up individually and show leadership for the team.

“It is a team sport. We feed off each other, and it is important for all of us to be on the same page and in the same state of mind,” Adams said. “In order to work as a team and go out there and perform together, we need to make sure everyone is involved in one way or another.”

For Adams and other former cheerleaders, working as a team comes naturally. Cheerleading is a team sport and, much like acrobatics and tumbling, requires every athlete to contribute their strengths to round out the team as a whole.

From the first practice in September to finals and every week in between, the women don’t stop supporting each other on and off the mat. Acrobatics and tumbling isn’t just based on their friendship during practice and meets, but also their relationships beyond the sport. Although every member of the team comes from diverse athletic backgrounds and have made various adjustments to acclimate to the sport, it’s also the one component that makes the team so unique.

“We really do have this really tight bond that forms so quickly in the beginning and just grows and grows and grows,” Adams said. “I think especially this year, it shows. We talk all the time and it’s so good, but there’s no pinpoint about what it is. It’s just this feeling that we all have and it’s something that I’ve never had on another team.”