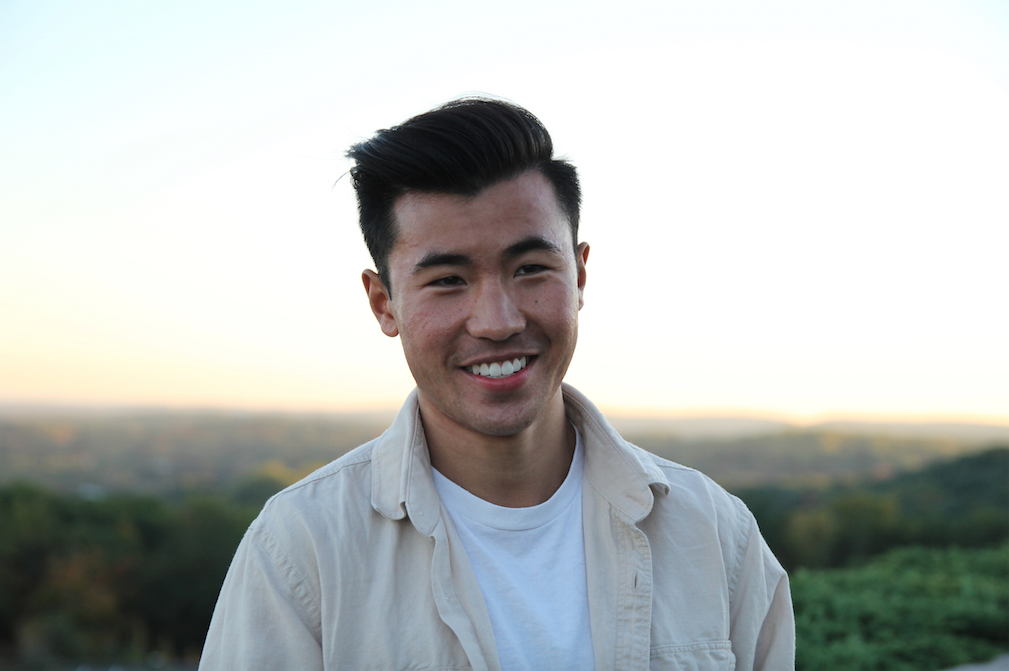

Cross-country runner Kyle Liang shares his story of doubt, depression and determination as a student-athlete

“Have you considered not running?”

I’d be lying if I told her I hadn’t.

It was December 2014, and my long-awaited five weeks off from school had finally arrived. I was sitting on the living room floor next to my mom, watching another episode of one of her crazy Chinese soap operas that, frankly, make no sense to me. Yet it was winter break, and I would only be home for few weeks, so if sitting through an hour of hysterical men and close-ups of women with watery eyes meant I got to spend some time with my mom for the first time since August, then someone get me a Snuggie and a hot cup of tea.

“I know that you’ve mentioned before not running your senior year. And I know how much you love theater. Why don’t you just quit the team next year instead? Give yourself a chance to do plays, dance…”

She’s right. I have other passions; why don’t I just quit the team now? What am I waiting for? I’m miserable.

I ended the first semester of my sophomore year with a nasty virus, an unintended weight loss, a patchy beard from a lack of care about my appearance, a disappointing finish to my cross-country season, an empty space on my wall where my regional championship bib number should have hung had I not lost my varsity spot on the team, and somehow still an impressive GPA. More importantly, I ended my first semester of sophomore year cringing at the thought of college, with an inability to feel satisfied, and a morbidity and hollowness that made me wonder if the fun-loving person I was in December of 2013 after my first semester freshman year would ever return.

I asked myself if this is how the remainder of my days as a college athlete would feel. When I got home the night after taking my last final, I sat down in my living room and told my dad that I didn’t want to go back to school. I wanted to cry but was too drained of energy and emotion to produce tears.

“Well I just thought I’d bring it up. You shouldn’t burn yourself out now. You still have two more years plus grad school.”

Quitting the team wasn’t an option regardless of whether I verbalized a desire to or not. My sport was as much a part of my life as an older sibling. Distance running was my mentor; it helped me grow; it shaped my character; it forced me to mature; it taught me essential life lessons. To give up my sport would be to leave behind a part of my identity like a piece of trash on the side of the road. My conscious would never allow that. I could never allow that.

And so with each practice I felt more bound to the sport I knew was largely the root of my misery. The sport I loved became my heaviest burden. I completed hour-long runs each day with my team in silence. The stress from my classes was affecting my ability to perform on the field, and my ability to perform killed my love for the sport, which, in turn, left me feeling depressed. Distance running brought my life joy. It gave me purpose and identity, and as my ability to run was affected, so was my ability to feel joy–I was losing sense of who I was and what I was meant to do. And as a student I was struggling. Cross-country was pulling too much time away from my studies. My studies were pulling too much time away from running. I could feel my mind and body being broken down in pieces too small to be put back together. Each week brought a new wave, smashing me against the hard rock wall that is college athletics. I was disintegrating.

On paper I knew I should be happier—I was running Division I and attending an academically respected university, yet the thought that I had every reason to be happy only made me more upset.

“I know, Mom. I’ll see how this semester goes.”

I started second semester with a shaven face, the weight I originally had before finals week in December (thanks to Mom’s cooking), and a new attitude. January 2015 became the start of a new approach to my athletics and academics. I decided that my health needed to become a priority again. December 2014 gave me the tiniest glimpse of how college students like Madison Holleran, track star for University of Pennsylvania who leaped off the ninth floor of a parking garage in January 2014, might have felt.

Fortunately, five weeks at home was the perfect remedy—I actually don’t mind watching Chinese soap operas anymore. For other students, five weeks may not be enough: family and friends cannot solve everything, and second semester may be only the start of a downward spiral that has no apparent end.

Mental health among student-athletes is too often overlooked. The combination of high academic expectations along with unhealthy physical demands, while holding the smile everyone expects from a kid who is lucky enough to be playing their sport at a great college, is dangerous. No athlete would deny that competing in college is an opportunity of a lifetime. However, I have no doubt in my mind that most athletes would agree when I say it does not always feel like one.

Follow Kyle on Twitter: @Kyle_Liang